On May 13, 1888, Brazilian Princess Isabel of Bragança signed Imperial Law number 3,353, a text containing just 18 words and two paragraphs. Still, it’s one of the most important pieces of legislation ever approved in Brazil. Called the “Golden Law,” it abolished all forms of slavery in our country.

For 350 long years, slavery was the heart of the Brazilian economy. According to historian Emilia Viotti da Costa, 40 percent of the 10 million African slaves brought to the New World came to Brazil. Slaves were so pivotal to our economy that Ina von Binzer, a German educator who lived here during the late 1800s, wrote: “In this country, the Blacks occupy the main role. They are responsible for all the labor and produce all the wealth in this land. The white Brazilian just doesn’t work.”

By 1888, abolitionism was a consensual cause, which had the support of most Brazilians – including several conservative sectors. The reason? Slavery had actually decreased due to the modernization of agriculture and increasing migration towards Brazil’s cities from rural locales.

The process that culminated in the “Golden Law” began nearly 70 years prior to 1888. From the moment of Brazilian independence, the country was pressured by England into abolishing its slave trade. However, in 1822, 1.5 million of our 3.5 million people were slaves. And slavery was not simply tolerated – it was strongly supported by all segments of society, including the Catholic Church.

Over time, though, England began seizing slave ships in the Atlantic Ocean, and even attacked a few ports in Brazil with the goal of forbidding slave trade. As a result, the Brazilian government passed a law declaring that all slaves were free upon reaching Brazilian soil. That being said, the government never did much to enforce the law.

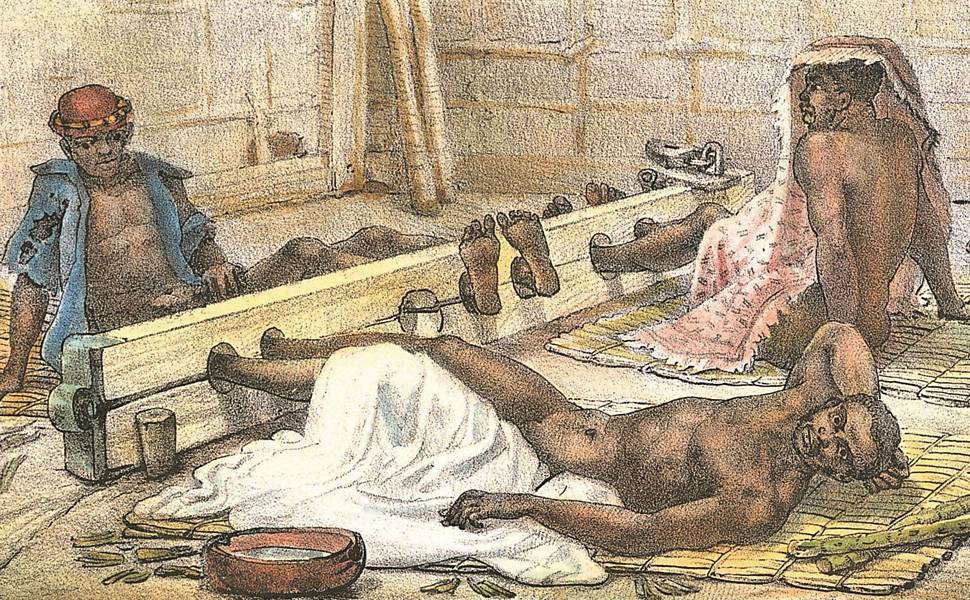

As British ships made life harder for traders, the supply of slave labor declined and slaves became more expensive. During Brazil’s early years, slave mortality was extremely high due to appalling housing and work conditions. As time went by, however, owners were forced to improve those conditions in order to preserve their slaves.

Landowners became increasingly aware that slave labor was making less and less economic sense. Paying low salaries to free men was in fact cheaper than maintaining slaves, for whom the owners were responsible. It was around this point that the Brazilian government decided to start to implementing policies with the aim of gradually reducing slavery, treading carefully to avoid disturbing the owners’ economic interests.

The gradual abolition

In 1871, the Brazilian Parliament passed the so-called “Free Womb Law,” declaring that all children born to slave women would be free. However, children had to work for their parents’ owners until they were adults in order to “compensate” the owners. At the time, many notaries – with the knowledge of local parishes – falsified birth certificates to prove that child slaves were born before the law passed. By the estimations of Joaquim Nabuco, a lawyer and abolitionist leader, thanks to this piece of legislation alone, slavery would be in effect in Brazil until the 1930s.

In 1884, a new law came into effect that freed slaves of 60 years old or more. This one was even more perverse than the latter, as it gave owners the power to abandon slaves on their own when they were less productive and more susceptible to diseases. Moreover, it was rare that a slave even made it to his or her 60th birthday.

The Church ended its support of slavery by 1887, and it was not long after that the Crown also started to position itself against it. On May 13, 1888, the remaining 700,000 slaves in Brazil were freed – and left on their own.

Abolitionist movement

Brazil’s abolitionist movement was timid and removed. First, this was because it was an urban movement at a time when most slaves worked on rural properties. But it was also because abolitionist leaders weren’t preoccupied with the aftermath of the abolition. There were no policies of integration, nor were there plans to help transition former slaves into true citizens. Indeed, the abolitionist movement was more concerned with freeing the white population from what had come to be viewed as the burden of slavery.

After slavery was finally abolished as an institution, however, the Brazilian government implemented a policy to whitewash the population. Black immigration was made illegal, and Brazil was to accept only white Europeans or Asian immigrants. Meanwhile, with nowhere to go and no other way to earn a living, many freed slaves entered into informal agreements with their former owners. Those amounted to food and shelter in exchange for free labor, thereby maintaining the status quo.

Still today, vestiges of the slave system can be witnessed in Brazilian society. It is not merely coincidence that while blacks and mixed-race people account for 53 percent of the population, they amount to two-thirds of our prison population and 76 percent of the poorest segment of our population.

Search

Search