With the election of retired military officer Jair Bolsonaro to the highest civilian post in Brazil, some observers fear that the military will ascend to a position they haven’t occupied since the country’s return to democracy in 1985. Some of the changes that have fuelled such concern have taken place at Abin, the Brazilian Intelligence Agency.

The previous incarnation of Abin didn’t leave good memories, yet one could argue that was not a past life at all, but an altogether different institution. Created in 1964, the National Intelligence Service, or SNI, has given enough source for nightmares. Its very own Dr. Frankenstein, General Golbery do Couto e Silva, reportedly said they “created a monster.”

According to journalist and researcher Elio Gaspari, author of a best-selling book series on Brazil under military rule, 20 years after the inception of SNI, Gen. Couto e Silva admitted that “We tried to create an information service, but we got screwed.”

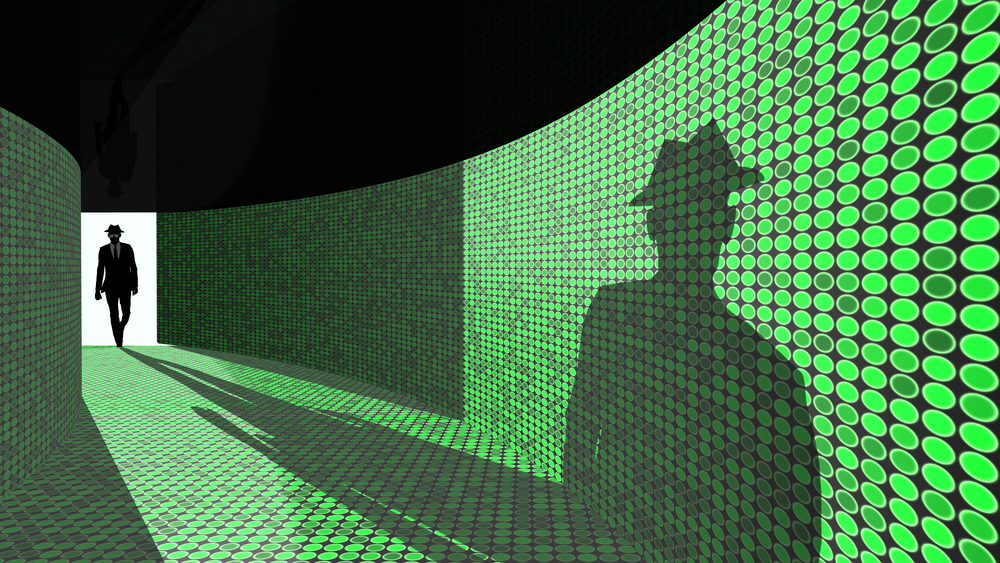

In yet another example of his 20/20 hindsight, the general said that such a line of work “disfigures people.” That, perhaps, could be said of most work that entails secrecy and deception, but the SNI was a special case. It was espionage turned inwards, aimed at identifying and destroying the opposition while spreading enough fear to discourage any manifestation of dissent. To that end, the SNI went far beyond gathering intelligence. It persecuted artists, promoted censorship, and kidnapped and tortured antagonists of the regime. It even created its own false-flag terror attacks.

As summarised by Mr. Gaspari, the SNI’s fronts of activity were many. “It got involved in appeasing land conflicts in the Northeast and among indigenous tribes in Bahia. It directed and organized mining in the Amazon;” it used the mined gold to make money in contraband and the currency black market; it raised money through coffee exports and processed uranium; it held secret arsenals that it considered putting to use “in a megalomaniacal invasion of Portugal in 1975; it distributed TV and radio channels, financed newspapers and magazines” and its top brass covered-up more than 100 political acts of terrorism, “from exploding bombs to torching news-stands which sold leftist newspapers”.

All of this is a far cry from the current iteration of Brazilian intelligence, but a few statements and gestures by government officials suggest Abin may be once again looking for political enemies, rather than bonafide criminals.

The SNI was extinguished in 1990 by Fernando Collor de Mello and replaced by the much smaller and civilian Department of Intelligence. It was only under Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the sociologist president, that Abin was created in 1999.

Abin works under direct orders of the president, but also under congressional supervision. On paper, it is covered by checks and balances, all while protecting the necessary secrecy that is the hallmark of government surveillance. Abin’s stated mandate is intelligence and counterintelligence, in order to “further national goals,” both against foreign...

Search

Search